A bit more interest in bonds

INVESTMENT SPECIALIST DAVID WARREN AT DISCRETIONARY INVESTMENT MANAGERS CHARLWOOD IFA SHARES HIS VIEWS ON MARKET EVENTS FOR NOVEMBER 2016

The past few months have witnessed a sea-change in the fixed interest market. The yield on the 10-year UK government bond has almost tripled from its August low of 0.50% to 1.45% (rising yields equal falling bond prices). This pattern has been reflected, to a greater or lesser extent, across global bond markets, despite ongoing buying by central banks in the UK, Europe and Japan.

Why defy the bankers now?

For the past few years we’ve been banging on about how central bank buying power has controlled the bond market, so what’s changed that has suddenly caused investors to defy the bankers’ billions and sell bonds?

Although Trump is getting much of the blame (or credit), the seeds were sown in the months preceding his election win. We started from a point where recent historically low yields left no margin of safety; only a small rise in yield would wipe out the year’s income, resulting in a likely overall loss.

The UK’s vote to leave the EU initially led to a further fall in yields as fears of a further slowdown in growth prompted a rate cut by the Bank of England with hints of more to come. But it didn’t take long for attention to focus on the likelihood that the currency’s sharp depreciation would lead to a rise in prices via more costly imports; this was supported by a coincident rise in inflation and a much sharper rise in factory input prices (often a warning of what consumers will see in the coming months).

Around the same time there was a growing sense of a shift in policy mix from monetary policy (low rates and quantitative easing) to fiscal policy (higher rates and more debt). This began with musings by the European Central Bank that additional QE and rate cuts were unlikely to yield further benefits; this was (mis) interpreted as signalling a potential tapering of the bond-buying programme. This was followed by hints (leaks) in the UK press that the new government would abolish its austerity programme in favour of massive spending on infrastructure. Across the pond both US presidential candidates were agreed on the need for a fiscal stimulus, with Trump promising twice as much as Clinton.

This double-whammy of a change in the supply and demand dynamic for bonds and a likely end to falling interest rates gave bond traders the confidence to grasp the nettle and send yields higher around the world.

Where next for yields?

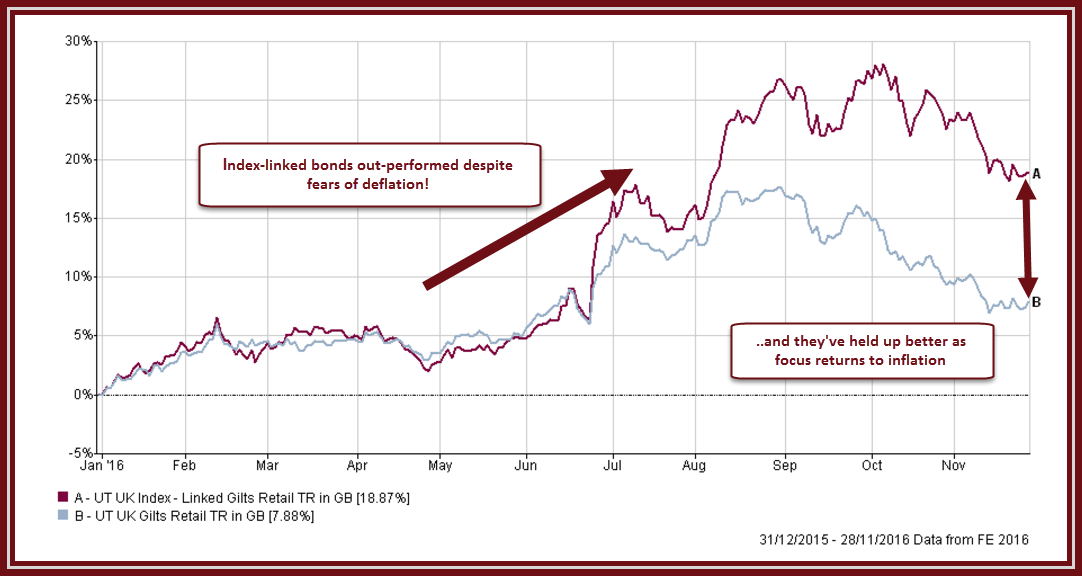

To put the recent move into perspective, gilt yields have only returned to their pre-referendum levels and are still showing a gain of around 7% for 2016; The Index-Linked sector is up by around 18% in a year dominated by a fear of deflation! Technical studies show that bond yields haven’t yet broken their downtrend line.

Current thinking is that the European Central Bank (ECB) will react to the recent rise in yields by extending its bond-buying programme for a further six months, but might announce a gradual tapering from that point. Europe is entering a period of uncertainty starting with an Italian Referendum this Sunday, followed by elections in Austria, The Netherlands, France and Germany over the next twelve months. Fears of a rise in Euro-scepticism could drive yields higher, though German bonds might benefit from a safe haven status, testing the ECB resolve.

In the US, the Federal Reserve is expected to raise rates at its December meeting; the real question is whether the accompanying statement will suggest a continuation of the slow and gentle approach to further rises or a need to up the ante in response to a pick-up in economic activity. In terms of the rise in government spending Trump has promised much, and he might mean some of it, but there’s some doubt over how much of an increase in spending will be permitted. This will have implications for the level of future growth in the economy and for the amount of bond issuance.

Outside of the US there appears to be no rush to consider raising rates; any such move could still be a matter of years away. Bank of England Governor Carney has shown his reluctance to raise rates but, paradoxically, this could see bond yields rise if he’s perceived to be taking a risk with inflation.

How are we placed?

We’ve been on record for some time now saying that fixed interest bonds offered little value at such low yields and that the risks of losing capital out-weighed the rewards of further gains. We were too early with that call but still felt comfortable with the decision.

On our portfolios that require fixed interest exposure we hold a spread of funds, typically with limited exposure to interest rate risk; these include corporate bonds, high-yield, index-linked and overseas bonds. We also hold a couple of funds that benefit from rising interest rates. Our income portfolios hold an emerging market bond fund which, despite a 6% fall after the US election, has steadied and is showing a 28% gain year-to-date.

We’re regularly reviewing our under-weight stance, re-visiting the arguments above, and more, but at these levels we still feel that even if there is a pick-up in demand for bonds again, the risk of future losses out-weigh the possible gains.